Setting up an innovation lab can be a bewildering experience. Our lab here in Armenia has been up and running for two years; during this time there’s been blood and tears but also our fair share of successes.

To take stock of our achievements and identify our failures we invited the lovely people at Futuregov to Yerevan. They published a fantastic report on the status on UNDP Armenia’s innovation activities perfectly articulating many of the issues that we are facing and set out a vision for us to truly mainstream innovation in everything we do.

Here is what we learned:

1. What to do: changing the organisation vs. changing the programme – or both?

If a Lab’s overarching task is to create more inclusive and human-centric public services and infrastructure, can this be best achieved by focusing directly on community projects, or indirectly through effecting a culture change within UNDP Armenia? For us, pursing both, the question became how can we get the balance right?

A report by Oxford University recently captured this same tension. Prioritising the dual imperatives of organisational and community change is often a strategic challenge.

Source: Refugee Studies Centre, University of Oxford

Early on we identified three user-groups: the government, the citizen, and UNDP. Working with the active citizen was easy, that’s where we started and where the lab has thrived. Instead, the real challenge began with the expansion from our citizen-users (community programming) towards internal (organisational) change – towards a cultural change. The lessons from our efforts towards internal change are the focus of the rest of this post.

Lesson: the two paths are very different – make sure to balance both without neglecting organisational change.

2. How to do it

Presenting a new paradigm of development practice can be an intensely political process; it also pushes us way outside our comfort zone. Added to this, within our office there were a number of legitimate concerns regarding the value citizen vs. expert input.

In trying to demonstrate the value of citizen-centric, desig-led approaches to development we were waiting for colleagues to seek us out. That didn’t work. Instead Futuregov suggested we just go out and conduct user research and present the results straight to the project teams, leaving the value on their table. This way, the benefits of new methodologies become available to everyone.

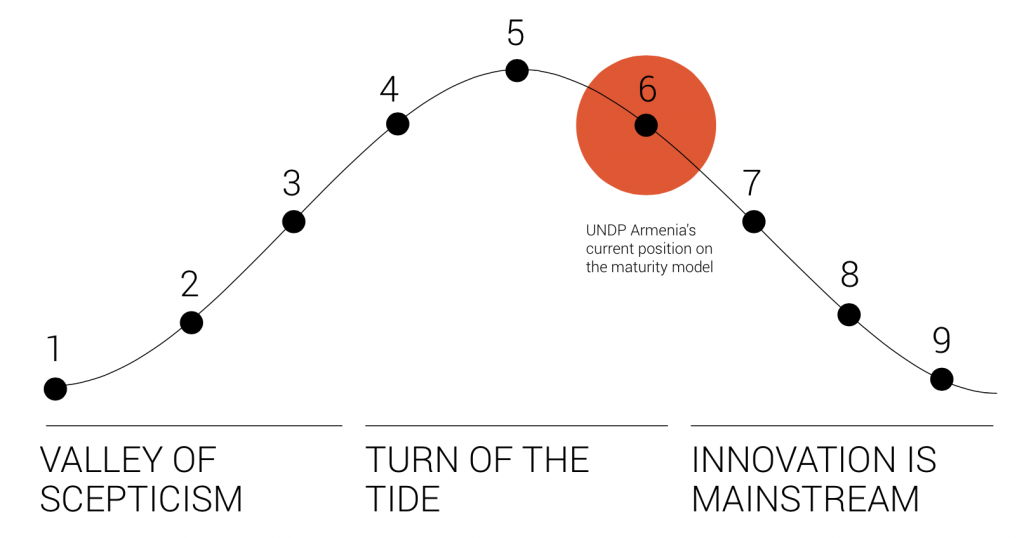

Achieving a critical mass transformational change is a two-way process and does not happen overnight. Yet today, we’re gradually reaching a point where every level of our operations contains elements of design-led innovation – see our recent co-design workshop with people with disabilities. Source: Futuregov, 2015

Lesson: don’t wait for engagement by your colleagues; apply design-led approaches to show the difference.

3. How to communicate it

By now Innovation Tourette’s has been well documented. The report highlighted that our lab is no different. Many of our colleagues just didn’t understand what we were talking about.

Part of what alienates people from doing things differently in the development sector in general is that they often don’t understand the terminology used to talk about it.

Since collaborating with FutureGov we’ve made a conscious effort to inject these terms with meaning, using artefacts and a helpful ‘innovation dictionary’ taped to the lab door, as well as through open workshops such as our recent event applying design thinking to environmental stewardship. There have been a couple of Damascene conversions since then.

Lesson: keep it simple where possible; fill terms with meaning through activities and artefacts.

4. How to collaborate

One of the key dangers of setting up an innovation lab is that it becomes just another ‘silo’, thus blocking the path to wider organisational change. Futuregov cautioned against this, suggesting that every project we are working on be co-owned by someone from the relevant portfolio. This is now reflected in our design principles – that everything we do should be owned by someone else.

At the same time, we were wary of overloading our colleagues with citizen-centric approaches. Our insistence on human-centred design was perhaps too much, too fast. For the coming months our focus will be directed towards demonstrating the value of insights generated by purely ethnographic user research.

Lesson: co-own and start slow.

5. Letting go of Innovation

We discovered that the lab needed to stop owning innovation. Many of our colleagues are already applying fresh and creative ideas to their projects, whether using ICT for disaster risk reduction or through SMS polling in local governance.

It seems unlikely that there is a country office in which nobody is doing anything differently. In any case, owning the label of innovation can easily become counterproductive to the message of doing things differently.

For us in the office this means not owning the label of ‘innovation lab’. Instead we’re focusing more on our citizen-centric approaches in crowdsourcing, open data, ethnographic research, human-centred design, game mechanics and foresight.

Lesson: ‘innovation lab’ may be a useful brand externally, but internally it can be harmful – be prepared to let go if necessary.

Today we’re witnessing a shift in governance; towards a relationship between citizen and state based more on empowerment. Kolba Lab is our vessel to achieve this shift in the governance of the development sector within Armenia. The time has come to get beyond our community of troublemakers! We hope these insights help you do the same.

By Claire Medina and George Hodge